2 April 2016

On this day in 1963 the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) released the Birmingham Manifesto. This short, sometimes forgotten document launched one of the most tumultuous periods in civil rights movement history: the Birmingham Campaign. Six weeks of nonviolent direct action generated a response so fierce that mainstream media still use its images of police dogs, fire hoses, and backlash bombings to signify racism at its worst.

The Manifesto, signed by president Fred Shuttlesworth and secretary Nelson Smith, challenged Birmingham’s citizens to live up to American ideals of equality and justice. For too long, the city’s black population had been “segregated racially, exploited economically, and dominated politically.” The ACMHR – modeled on the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization behind the successful 1955-56 Bus Boycott – had tried unsuccessfully since its 1956 founding to negotiate with white leadership for integration of public facilities and local businesses. The result: “broken faith and broken promises.” Although the group did not spell out specifics of an intended “direct action thrust,” the city found out the next day when demonstrations began.

In retrospect, the ACMHR’s timing proved both lucky and ironic.

The group distributed the Manifesto as handbills the day after the 1963 mayoral elections, hoping that a new city government might bring new results. What the ACMHR did not count on was a contested election, where the old form of government (a city commission) refused to leave office for its replacement (a mayor and city council) to come in. For a while Birmingham had two governments, effectively leaving no one in charge. The ACMHR was happy to take advantage of the power vacuum with strategic chaos. One day might bring sit-ins of downtown lunch counters and the next, a march. Sundays saw black visitors kneeling in front of white churches to see which ones admitted them. Any given day brought a few dozen picketers before a department store or hundreds of protesters filing from a church toward downtown. White leadership rarely knew what to expect.

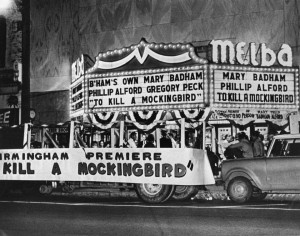

If the ACMHR did not anticipate catching white Birmingham off balance, the group also did not know that its “direct action thrust” of April 3 coincided with the highly anticipated local premiere of the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird featuring local residents Mary Badham as Scout and Phillip Alford as her brother Jem. Based upon Harper Lee’s 1960 novel of the same title, the film’s sentimentalized version of race relations would cause a generation of Southerners to “weep clandestinely,” as Diane McWhorter puts it, “about the racial guilt we shared in rooting for a Negro man” (322).

Tears, however, rarely led to meaningful change.

May 10, 1963 saw a truce in the Birmingham Campaign. Federal negotiators, moderate black leaders, and white businessmen worked out a compromise where downtown stores and restaurants agreed to desegregate and hire black workers. ACMHR president Shuttlesworth, injured by a blast of water from a fire hose a few days earlier, at first denounced the compromise as a sellout then checked out of the hospital to present the compromise’s terms to the media. Joining him at the microphones to create the sense of a unified black voice were Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) president Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Mid-press conference, Shuttlesworth passed out from exhaustion and pain. King continued fielding questions.